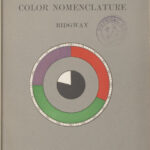

Desirous for a book that would finally standardize colors and their names, Robert Ridgway, an ornithologist, took upon himself the mammoth task of producing just such a volume – covering more than a thousand colors. The enduring value of his labor is evidenced by the naturalists and artists who, a century later, continue to use it as a standard reference. Much of this value must certainly lie in the work’s impressive display of color itself: distributed among 53 plates is a true sample for every one of the 1,115 colors Ridgway has named.

The challenge of producing stable true color samples for publication is daunting, and an MIT librarian seems to have appreciated the risk of color loss: a handwritten note in our copy directs the reader to a warning that the samples should be protected from prolonged exposure to light.

Perhaps even more daunting, however, is the challenge of imposing standard naming conventions on colors that have already been marketed under countless proprietary names. “Most of them are invented,” Ridgway writes of trade names of colors, “apparently without care or judgment, by the dyer or manufacturer of fabrics, and are as capricious in their meaning as in their origin; for example: such fanciful names as ‘zulu,’ ‘serpent green,’ ‘baby blue,’ ‘new old rose,’ ‘London smoke,’ etc., and such nonsensical names as ‘ashes of roses’ and ‘elephant’s breath.’”

This sort of confusion no doubt continues today – you need only consult a box of crayons – but Ridgway’s work paved the way for the recourse found in today’s international color standards.