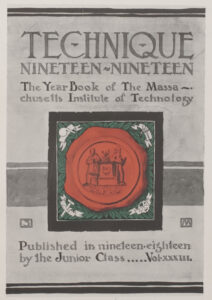

We’ve all seen yearbooks, and we know what to expect from them. They follow a formula that doesn’t vary much from year to year: there’s usually a dedication, then a list of faculty; formal portraits of the senior class; maybe some candid shots; humorous bits about tough professors or difficult courses; sections on clubs, activities, and athletics. It’s boilerplate, and it can seem as though the only thing that actually changes from year to year is the photos.

And sure enough, the MIT yearbook published in 1918 (by and for the class of 1919) covers the usual territory. It features, for example, a lengthy section on that year’s Tech Show, Let ‘er Go. In keeping  with tradition, all roles in this original musical were played by men, including the roles of Helen Barnes (the heroine), Mrs. James P. Barnes (Helen’s mother), Pussy Willow (a Quaker girl), and the “Premiere Danseuse.”

with tradition, all roles in this original musical were played by men, including the roles of Helen Barnes (the heroine), Mrs. James P. Barnes (Helen’s mother), Pussy Willow (a Quaker girl), and the “Premiere Danseuse.”

Sometimes, though, a yearbook upends our expectations. It isn’t that it departs from the formula; rather, the content within that formula happens to capture a snapshot of a tumultuous time. Where we expect a uniformly blithe and irreverent tone, we instead encounter a sudden solemnity.

In Technique 1919, we meet with the unexpected on only the third page of the volume:

The dedication of this volume is accorded to those sons of Technology who in serving their country have honored their alma mater

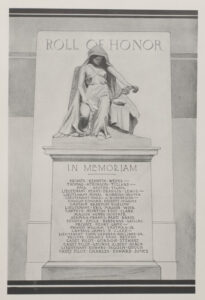

It’s fairly general, yet somber and clearly respectful. But just two pages later, things become more serious still, and much more personal. It’s a “Roll of Honor” – the names of 22 individuals, all of them presumably young and many of them presumably known personally by the young people who prepared this volume. Enthroned above the list is a metaphorical figure of grief. These are the names of young men who have been killed in the Great War.

In 1918, with the world engulfed in a conflict that was unprecedented in its capacity for carnage, MIT’s junior class seemed sensitive to the environment in which they’d be publishing their own edition of a book that’s usually intended to capture nothing more than the pleasantest of memories.

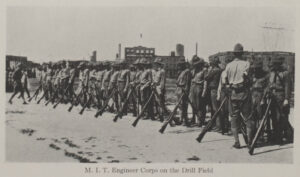

World War I permeates the 1919 Technique. A 34-page section captures MIT’s all-out commitment to the war effort: the Institute now hosted an MIT Engineer Corps, a Cadet School for Ensigns, the U.S. Army School of Military Aeronautics, a Senior Battalion, a Technology Ambulance Unit, a Navy Aviation Detachment … MIT’s entire campus, in its still-new Cambridge setting, had been placed on a wartime footing. In fact we’re told that “President Maclaurin formally put the Institute, its plant, equipment, and faculty at the disposal of the government, and informed the War and Navy Departments of Technology’s resources.”

World War I permeates the 1919 Technique. A 34-page section captures MIT’s all-out commitment to the war effort: the Institute now hosted an MIT Engineer Corps, a Cadet School for Ensigns, the U.S. Army School of Military Aeronautics, a Senior Battalion, a Technology Ambulance Unit, a Navy Aviation Detachment … MIT’s entire campus, in its still-new Cambridge setting, had been placed on a wartime footing. In fact we’re told that “President Maclaurin formally put the Institute, its plant, equipment, and faculty at the disposal of the government, and informed the War and Navy Departments of Technology’s resources.”

MIT had moved to its Cambridge campus in 1916. It wouldn’t be long before the Institute would find it necessary and fitting to transform “Lobby 10” – one of its grandest spaces, overlooking the Great Court, the Charles River, and the Boston skyline beyond – into a memorial to those killed in World War I. Engraved into the lobby’s marble wall is a roster which, having begun with the list in this yearbook’s “Roll of Honor,” would grow to contain the names of dozens and dozens of MIT alumni killed during what was called at the time “the war to end wars.”

And that lengthy roster in Lobby 10, in turn, has now been joined by memorials to those lost in the numerous wars that have come since.