While it’s best known for science (and for its scientists), MIT also boasts an impressive array of musical talent. Nearly half of MIT’s undergraduates participate in the Music Program, and there are dozens of active music-performance groups on campus.

Of course not everyone plays music, but nearly everyone can appreciate it. Today’s featured item, How to Listen to Music, provides instruction for the non-musician in how to listen more effectively, and therefore, at least in theory, with more enjoyment.

Henry Krehbiel (1854-1923) was a notable music critic in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Though he lacked formal music training, Krehbiel worked as the music editor of the New York Tribune for nearly 40 years. From that post he helped  popularize the music of Wagner, Brahms, and Tchaikovsky in the United States. Toward the end of his life, however, he would criticize the modern sounds of Stravinsky and Schoenberg.

popularize the music of Wagner, Brahms, and Tchaikovsky in the United States. Toward the end of his life, however, he would criticize the modern sounds of Stravinsky and Schoenberg.

As a largely self-taught critic, Krehbiel encouraged others to think about music intelligently. He strove to convince the public that music was “tangible” and could be described in clear language. As he laments in one chapter, “I have been told that there are many people who read the newspapers on the day after they have attended a concert or operatic representation, for the purpose of finding out whether or not the performance gave them proper or sufficient enjoyment.”

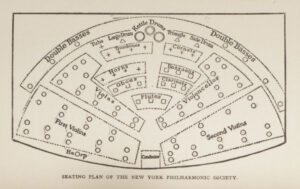

His book is meant to provide a toolkit for those who enjoy music, but who lack the vocabulary to express why they do. By describing the various instruments in an orchestra, explaining basic rhythmic motifs, exploring the history of choral music in America, and demystifying dynamic and style markings, Krehbiel helps his readers feel more confident in forming their own opinions about musical performance.

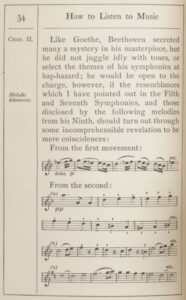

Although the book is intended for “untaught lovers of the art,” there are many examples of printed music to illustrate the author’s points. As he explains in the text accompanying the first example, “It will be as apparent to the eye of one who cannot read music as it will to his ear when he hears this melody played, that it is built up of two groups of notes only.” Still, it seems Krehbiel may be taking for granted that his audience would be able to comprehend printed music … or simply assuming that everyone has handy access to a friendly pianist who can help with the examples.

At the end of the volume, Krehbiel includes portraits of top New York musicians of his day, posed in photographs with some of the instruments discussed. One of those pictured is Victor Herbert, composer of the wildly successful Babes in Toyland. Herbert also wrote Naughty Marietta (source of the oft-parodied song “Ah! Sweet Mystery of Life”), several other operettas, and music for the Ziegfeld Follies.