Francis LaFlesche was the son of the last Omaha head chief. He eventually became an ethnologist for the Bureau of American Ethnology at the Smithsonian Institution. Among many notable accomplishments, his effort to capture and preserve a record of tribal culture yielded hours of recordings of Osage chants and ceremonies that would otherwise have been lost forever. The Library of Congress, which now holds the recordings, considers LaFlesche’s Osage work “very probably the most exhaustive documentation of complete Indian ceremonies ever produced.”

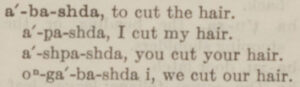

This volume, published the  year he died, remains the definitive dictionary of the Osage language some seventy years later.

year he died, remains the definitive dictionary of the Osage language some seventy years later.

The book belonged to Ken Hale, who for decades was among the most distinguished (and well-loved) members of MIT’s faculty. Famous for his ability to learn languages easily, thoroughly, and with astonishing speed, Hale was a professor of linguistics specializing in the languages of indigenous populations in Australia, Central America, and the American Southwest. Toward the end of his career, he was working with New Englanders on preserving the language of the Wampanoag tribe, among others.

Like LaFlesche, Hale was deeply committed to rescuing endangered languages – and cultures – from oblivion. As Hale himself put it: “The loss of local languages and of the cultural systems which they express, has meant irretrievable loss of diverse and interesting intellectual wealth. Only with diversity can it be guaranteed that all avenues of human intellectual progress will be traveled.”

Known for his humility and warmth as well as for his brilliance, Ken Hale was also a determined activist. When he died in 2001, at the age of 67 and just two years after his retirement, he was remembered by Institute Professor Noam Chomsky as “a person of honor and courage, who dedicated himself with passion and endless energy to protecting the rights of poor and suffering people throughout the world.”

Hale was born in Chicago but moved to Arizona at the age of six; while in high school, he happened to room with a Hopi boy. He learned the boy’s language, and found his life’s work. LaFlesche was born on a bleak reservation, the son of a tribal chief. To state the obvious, these two men came to their callings from vastly different backgrounds.

They also worked in different ways and in different venues, and of course they never met: LaFlesche died a few years before Hale was born. Yet the passion they shared was in certain ways all but identical: they were both deeply committed to saving something they knew was precious and, as each of them keenly understood, extremely fragile. Both LaFlesche and Hale devoted their lives to preventing the extinction of specific systems of cultural expression – appreciating, as they did, the unique capacity of each culture’s language to convey that culture’s own particular way of perceiving the universe.

Francis LaFlesche’s Dictionary of the Osage Language sits in the open stacks of the Humanities Library, bound in a plain library-cloth cover that was placed on it to protect the equally plain paper wrapper in which it was originally issued. It’s among the hundreds of books Ken Hale gave to the MIT Libraries, and bears his signature. The book wasn’t produced to be fancy; it’s a product of the U.S. Government Printing Office. Yet this most unprepossessing of volumes still manages to be among the MIT Libraries’ most resonant objects.