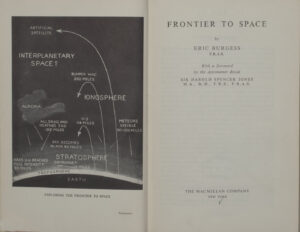

Published: New York, 1956

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union  launched the world’s first artificial satellite, Sputnik I – the event that would jumpstart the Space Race. Only a month later, on November 3, the Soviets launched Sputnik II, this time with a dog on board.

launched the world’s first artificial satellite, Sputnik I – the event that would jumpstart the Space Race. Only a month later, on November 3, the Soviets launched Sputnik II, this time with a dog on board.

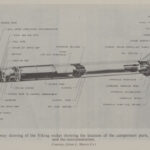

Frontier to Space, a look at high-altitude rocket research in the United States, was published in the year prior to these game-changing events.

In the book’s final chapter, Eric Burgess touches on projected developments:

It has been postulated that artificial satellites of this planet could be established and diverse proposals have been put forward to this end. Many of these have been extremely ambitious and verging on the impractical, but there have, on the other hand, been suggestions for small instrumented vehicles which do need serious consideration.

He goes on to predict that “while we are not likely to see manned space voyages for some considerable time yet … probe rockets should prove valuable tools in astronomical and astrophysical research during the coming fifty years.”

But manned space travel was to come much sooner than Burgess imagined: just five years after this book’s publication – on April 12, 1961 – Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin completed an orbit of the Earth. And a mere eight years after that, on July 20, 1969, Americans Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin (MIT Sc.D., 1963) became the first humans to set foot on the moon.

But manned space travel was to come much sooner than Burgess imagined: just five years after this book’s publication – on April 12, 1961 – Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin completed an orbit of the Earth. And a mere eight years after that, on July 20, 1969, Americans Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin (MIT Sc.D., 1963) became the first humans to set foot on the moon.

While the launch of Sputnik served as a wakeup call for much of the United States regarding space exploration and rocket development, MIT was already hard at work educating the scientific and technological leaders who would put the U.S. on the moon in advance of the Soviet Union. In the year this book was published, nearly a quarter of MIT’s incoming freshmen claimed they intended to major in physics. It’s not surprising that the MIT Libraries own this book, and its date stamp indicates that it was received on November 4, 1957: a month to the day after Sputnik I was launched.

In addition to his numerous monographs,  Burgess ghostwrote many NASA booklets and educational materials. He’s also noted for suggesting to Carl Sagan that Pioneer 10, the first spacecraft to leave our solar system, should carry a visual message from humans to extraterrestrials who might encounter the craft. The result was a plaque with an image of a human male and female that was affixed to Pioneer 10’s antenna support struts. We can thank Burgess for sending our first formal greeting to non-Earth intelligence.

Burgess ghostwrote many NASA booklets and educational materials. He’s also noted for suggesting to Carl Sagan that Pioneer 10, the first spacecraft to leave our solar system, should carry a visual message from humans to extraterrestrials who might encounter the craft. The result was a plaque with an image of a human male and female that was affixed to Pioneer 10’s antenna support struts. We can thank Burgess for sending our first formal greeting to non-Earth intelligence.