Young people today might have difficulty actually believing what daily life was like for people of color in the segregated South as recently as 50-odd years ago. Assaults on individual dignity were wide-ranging and ubiquitous. A case in point: the public bus system in Montgomery, Alabama in the 1950s.

In Stride Toward Freedom, Martin Luther King, Jr. writes:

Even if the bus had no white passengers, [but was] packed throughout, [black passengers] were prohibited from sitting in the first four seats (which held ten persons).

The indignities didn’t stop there. Upon boarding, people of color had to sit in the back, and then occupy seats moving toward the middle as the bus filled. White people took seats at the front, and then filled rows moving back toward the middle until the bus was full. Under no circumstances was a person of color allowed to occupy the same row – let alone the same seat – as a white person. If a white person needed a seat, an entire row of black riders was cleared, and those  passengers had to stand. If a person of color refused to stand when a white person wanted a seat, he or she was arrested.

passengers had to stand. If a person of color refused to stand when a white person wanted a seat, he or she was arrested.

Stride Toward Freedom, King’s first book, tells the story of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a milestone of the civil rights era. The event made a national leader of Martin Luther King, Jr., and a national icon of seamstress Rosa Parks.

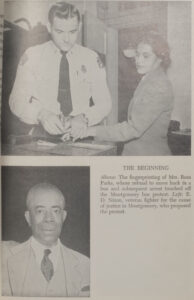

On December 1, 1955, after an exhausting day at work, Parks was told to surrender her seat to a white male passenger. But history was about to be made: “Mrs. Parks quietly refused. The result was her arrest.”

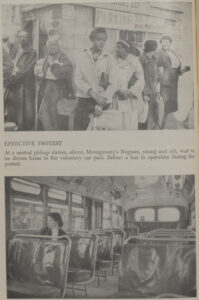

Like Rosa Parks, the black community had had enough. When word of Parks’ arrest shot  through Montgomery, the black citizenry fought back by boycotting a bus system that relied on their fares for its operating income. It was a dangerous gamble: such a boycott would have to be supported nearly universally if it were to succeed. And there would be physical danger as well: King’s home was firebombed, as were several black churches.

through Montgomery, the black citizenry fought back by boycotting a bus system that relied on their fares for its operating income. It was a dangerous gamble: such a boycott would have to be supported nearly universally if it were to succeed. And there would be physical danger as well: King’s home was firebombed, as were several black churches.

The black community did support the boycott, and the most moving part of this story lies in the thousands of nameless individuals who risked far more than we may think, day in and day out for a full year, in order that generations who followed might experience lives of increased civility and grace.

The boycott meant that people who already worked at difficult jobs for very long hours would face even longer days. It meant that individuals already forced to endure indignities and petty interference on a daily basis would face further inconvenience and trouble. It meant that men and women  whose daily lives were already a struggle against ignorance and meanness would have to endure even more of each.

whose daily lives were already a struggle against ignorance and meanness would have to endure even more of each.

But endure they did. They persevered in the unglamorous work of maintaining a boycott that forced them to walk miles in rain, heat, and cold – and they did so in the knowledge that their actions would increase the already-constant threat of physical violence against them.

Rosa Parks’ arrest, trial, and conviction set off a chain of events that would lead, a year later, to a Supreme Court case that found Montgomery’s segregated bus system unconstitutional.

In King’s words:

There comes a time when people get tired of being trampled by oppression … when people get tired of … exploitation and nagging injustice. The story of Montgomery is the story of 50,000 such [people] who were willing to substitute tired feet for tired souls, and walk the streets of Montgomery until the walls of segregation were finally battered by the forces of justice.