Donlyn Lyndon, the author of this guide to Boston’s built environment, headed MIT’s Department of Architecture from 1968 to 1975, and he knows his subject. The City Observed is more than just one expert’s opinion of Boston and its buildings, though. It’s also an extremely readable introduction to the language of architecture itself, and it includes a brief, highly useful, illustrated guide to common architectural elements.

But it’s in Lyndon’s assessment of Boston’s buildings that the  book shines. Of course he’s an astute critic of architectural form and function, but he’s a terrifically entertaining writer, too. Lyndon’s that rare author who can keep you turning pages even as he educates you by stealth.

book shines. Of course he’s an astute critic of architectural form and function, but he’s a terrifically entertaining writer, too. Lyndon’s that rare author who can keep you turning pages even as he educates you by stealth.

The book’s a reasonable size and thus portable, and it can be great fun to pick a Boston neighborhood and walk through it with a copy of The City Observed in your backpack. (The book is arranged by city sections.) Buildings that might previously have escaped your notice are suddenly revealed for the fascinating structures they are. Even a building that everyone knows to be great – the Boston Public Library, for example – acquires freshness and a new magnificence when it’s surveyed with this book in hand.

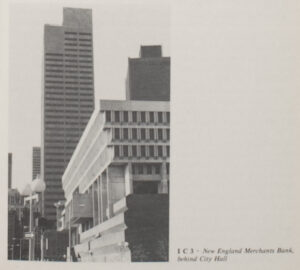

The author is full of surprises: a skyscraper that you’ve probably never even noticed is “unequivocally the best high rise in Boston” according to Lyndon, and he lists very good reasons for that pronouncement. (The mystery building is pictured in the “150 Years” entry you are now reading.)

The author is full of surprises: a skyscraper that you’ve probably never even noticed is “unequivocally the best high rise in Boston” according to Lyndon, and he lists very good reasons for that pronouncement. (The mystery building is pictured in the “150 Years” entry you are now reading.)

He likes the widely-unloved Boston City Hall – he calls it “an astonishing building” – and he’s prepared to defend his opinion. Still, Lyndon isn’t blinded by affection: he’ll grant that the Brutalist 1968 structure is “just not friendly.”

He recounts the dramatic history of the John Hancock Tower, whose early years were plagued by a problem with its windows – a serious problem indeed for a 60-story building whose surface consists entirely of glass. The stigma of its early inability to hang onto its windows has finally faded, and the sleek rhomboid designed by Henry Cobb of I.M. Pei & Partners is now recognized as a masterpiece of skyscraper siting and design. In 2011 it won the AIA’s prestigious “25 Year Award.”

But the last word on the tower can only belong to Donlyn Lyndon: it may or may not be an “icily magnificent” building that “borders on the occult,” but it’s impossible to argue with Lyndon when he asserts that, to the street-level viewer of the John Hancock Tower, “it would seem that there is no weight in this world, just as there is nothing to come up against except your own reflection and haunting memories of the fragility of glass.”