To mark the official 150th anniversary of MIT’s founding in 1861, the Institute held a massive “Next Century Convocation” on April 10, 2011 at the Boston Convention and Exposition Center.

During the festivities, the renewal of MIT’s charter – a reaffirmation of the Institute’s mission – was signed by President Susan Hockfield. Also signing were MIT’s two Presidents Emeriti, along with representatives from the MIT Corporation, the faculty, the student body, and the staff. Each of them endorsed the document – a digital “iCharter” – on an iPad.

Since May of 2010, The Lewis Music Library has made an iPad available for loan. (Currently the library is circulating an iPad 2.) It’s loaded with music apps, and with thousands of clips from new CDs in the library’s extensive collection. The iPad does a lot of very cool things right out of the box, too.

A centrally important part of the MIT Libraries’ job is to make information as accessible as possible and to deliver it in the most appropriate way. So of course the Libraries provide tens of thousands of electronic journals and databases, access to GIS and social sciences data, digital collections, and countless other resources to serve MIT’s voracious appetite for information. Providing a tool like the iPad fits comfortably within the Libraries’ tradition of welcoming new technologies and embracing new ways to serve documents, images, and data.

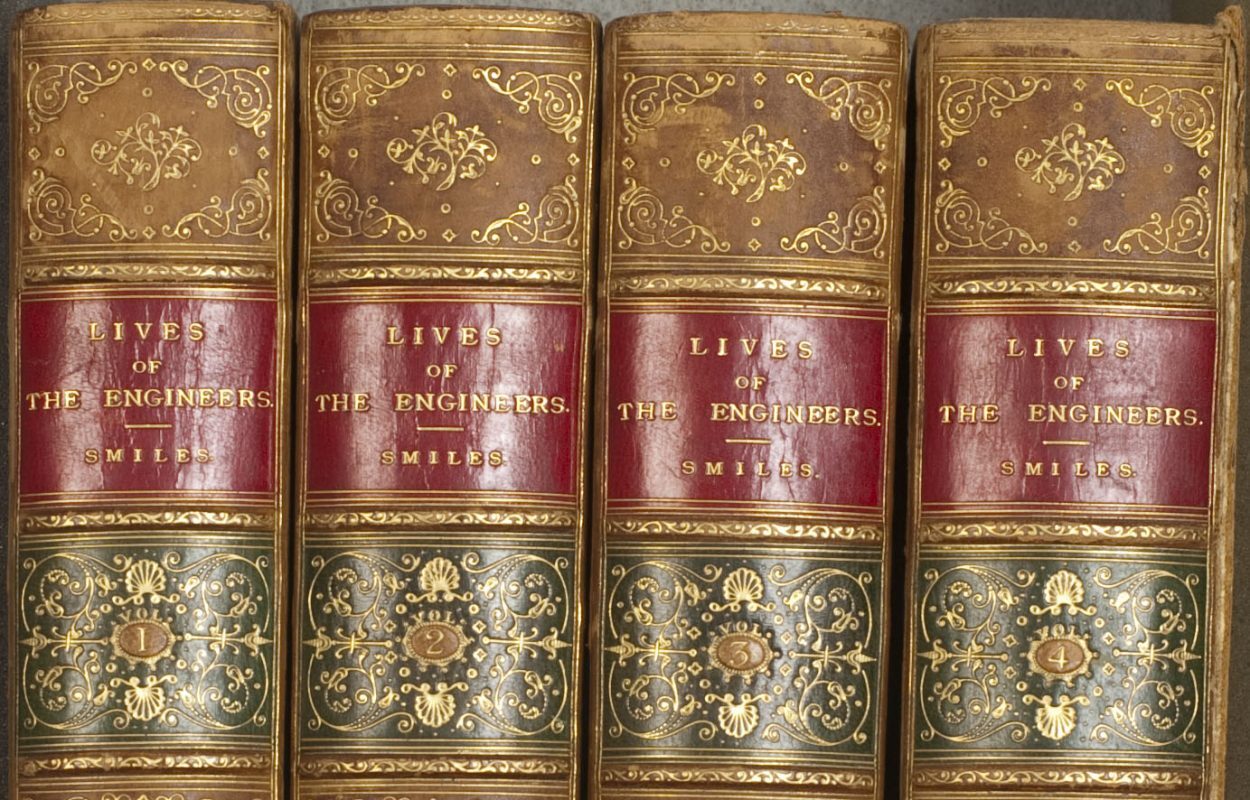

During research for “150 Years in the Stacks,” as we took a glance backward at the Libraries’ rich holdings, it was fun and occasionally thrilling to stumble across tangible materials we just didn’t expect to encounter. Of course digital information is crucially important to the work being done in a place like MIT. But happily there’s still room in major research libraries like ours for publications which, though they may show obvious signs of having been well-used, will sometimes wear that history with a touching eloquence.

An antislavery tract is an evocative historical document, particularly if it was written by a Virginian whose home is now an official Underground Railway site. When the author has inscribed it warmly to his friend, MIT founder William Barton Rogers, it’s a unique treasure for the Institute. You can certainly digitize such an object, but it won’t be the same as holding the original in your hand.

To be appreciated fully, some things just need to be experienced physically and in close proximity. John Stuart Mill’s 1880 Political Economy is available digitally, but our copy – a study in obsessive note taking – still has to be seen to be believed. How can any  photograph convey the mindboggling skill required to create a 200-pages-plus miniature book? To enjoy a book with moveable parts, well, you need to be able to move those parts. A booklet on radar can be a dry thing, but when it contains the signatures of a team of people who seem to have done as much as anyone did to win World War II, it becomes a deeply poignant document.

photograph convey the mindboggling skill required to create a 200-pages-plus miniature book? To enjoy a book with moveable parts, well, you need to be able to move those parts. A booklet on radar can be a dry thing, but when it contains the signatures of a team of people who seem to have done as much as anyone did to win World War II, it becomes a deeply poignant document.

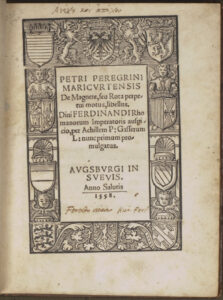

There simply is no substitute for the experience of seeing, touching, and yes, even smelling a treasure like the Libraries’ copy of Peregrinus’ exceedingly rare De Magnete, published in Augsburg in 1558.

There simply is no substitute for the experience of seeing, touching, and yes, even smelling a treasure like the Libraries’ copy of Peregrinus’ exceedingly rare De Magnete, published in Augsburg in 1558.

An iPad, on the other hand, gives you access to “150 Years in the Stacks.”

We’ll call it a toss-up.