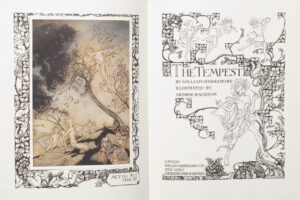

Published: London and New York, 1926

Countless people love Shakespeare’s Tempest. As with so much of Shakespeare, there are also innumerable people who don’t think they know the play at all but who still, in a sense, can be said to love it too: it’s filled with such beautiful imagery and such gorgeous poetry that pieces of it have become treasured parts of our shared language.

Full fathom five thy father lies

Of his bones are coral made:

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange. (I.ii, 397-402)

We are such stuff

As dreams are made on; and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep. (IV.i, 148-150)

O wonder!

How many goodly creatures are there here!

How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world

That has such creatures in’t! (V.i, 182-185)

Still, it’s unlikely that anyone who ever bought this specific edition of the play was interested primarily in Shakespeare’s poetry. This is a book that was sought after for its pictures.

Arthur Rackham was among the most successful illustrators of his day – the Grove Dictionary of Art hails him as “one of the great illustrators of the 20th century.” Of the fifty-plus books he illustrated, most were for children. His work was also sold in fine galleries, and he earned a very handsome living with his pen and brushes.

Arthur Rackham was among the most successful illustrators of his day – the Grove Dictionary of Art hails him as “one of the great illustrators of the 20th century.” Of the fifty-plus books he illustrated, most were for children. His work was also sold in fine galleries, and he earned a very handsome living with his pen and brushes.

He created this numbered, signed edition of The Tempest in 1926, at the peak of his career. But what’s most interesting about Rackham’s Tempest is what he chose not to emphasize. He ignored the play’s most beautiful poetry in order to focus on images that best suited his talents and predilections.

Rackham has chosen to illustrate very few of the play’s most moving and poetic moments. Instead, he concentrates almost entirely on passages that describe, or are spoken by, the sprites and fantastical creatures in the play. The “airy spirit” Ariel is Rackham’s star and is pictured repeatedly, while the mortal heroine Miranda is shown only twice. Prospero – a deeply resonant figure who many see as a stand-in for Shakespeare himself – may be capable of “rough magic,” but he is still an adult human. He is therefore banished from the illustrations altogether.

The result is strange. The artist’s (admittedly lovely)  illustrations shine a spotlight on some of the play’s least memorable characters, scenes, and lines.

illustrations shine a spotlight on some of the play’s least memorable characters, scenes, and lines.

Rackham’s most enduring legacy has been his impact on generations of fantasy and science fiction illustrators, in whose work his influence is still visible. He made his reputation and his fortune with books of fairy tales and fantasy stories for children. So perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that such an individual would focus on the nonhuman presences in a work that, for all its fantastic elements, remains one of Shakespeare’s most touchingly human plays.