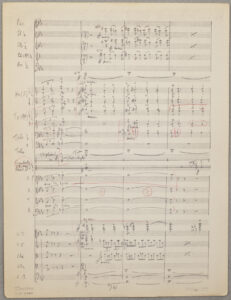

Published: New York, 1968 (original version premiered: Cambridge, Mass., 1955)

“Freedom is a noble thing!”

That is the first line intoned by the chorus in the finale of Aaron Copland’s Canticle of Freedom, a piece commissioned by MIT for the 1955 dedication of Kresge Auditorium and the MIT Chapel.

Famed modernist architect Eero Saarinen designed both the domed, 1200-seat auditorium and the cylindrical, windowless chapel that sits near it within a concrete moat. On May 8, 1955, James R. Killian Jr., president of the Institute, accepted the buildings. During the festivities, Copland’s Canticle was conducted by Klaus Liepmann, the founder of MIT’s music program, and was performed by the combined forces of MIT’s choral society, glee club, and symphony orchestra.

Freedom had surely been on Copland’s mind when he found himself ensnared in the McCarthy-era political witch hunts. On April 4, 1949, Life magazine published a spread entitled “Dupes and Fellow Travelers Dress Up Communist Fronts,” which included 50 photo portraits, including Copland’s own. The article accused these subversive but “innocent dupes” of lending “glamour, prestige [and] the respectability of American liberalism” to the Communist Party.

Copland might very well have felt proud of the company in which he found himself: Dorothy Parker, Arthur Miller, Langston Hughes, Albert Einstein, Norman Mailer, Susan B. Anthony II, Lillian Hellman, and Copland’s protégé Leonard Bernstein were among the “dupes” pictured with him in the Life article.

Copland might very well have felt proud of the company in which he found himself: Dorothy Parker, Arthur Miller, Langston Hughes, Albert Einstein, Norman Mailer, Susan B. Anthony II, Lillian Hellman, and Copland’s protégé Leonard Bernstein were among the “dupes” pictured with him in the Life article.

A few years later in 1953, Illinois Representative Fred Busbey, a virulent anticommunist, denounced the inclusion of Copland’s A Lincoln Portrait in President Eisenhower’s upcoming inauguration festivities. The piece was indeed dropped from the program despite objections from Claire Reis of the League of Composers, who wrote that “this is the first time, as far I know, that a composition has been removed from a concert program in the United States because of the alleged political affiliations of a composer.” Not long after, Copland received the inevitable invitation, by telegram, to appear before Senator Joseph McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee. Copland’s biographer, Howard Pollack, writes that he “talked his way around most questions and avoided naming names.”

Despite a subsequent spate of canceled lectures and concerts, Copland’s reputation suffered no lasting damage. The arts and university communities rallied around him; he received honorary doctorates from Princeton and Brandeis during the 1950s, as well as membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Certainly MIT’s commissioning Copland to compose the Canticle at that time was a direct affirmation of academic, artistic and political freedom.

The piece’s orchestral writing is relatively uncomplicated, but for the lucky percussionist, it includes a large battery of percussion: snare and base drum, wood block, slapstick, triangle, cymbals (suspended and crash), gong, glockenspiel, xylophone, tubular bells and tam-tam. The piece also includes a choral coda.

After its premiere at MIT, Boston Globe critic Cyrus Durgin declared that

the general style of this piece, during the lengthy orchestral portion, is [reminiscent] of Appalachian Spring. The familiar elements of that style, its rhythmic motion, diatonic and somewhat squarish melodies, harmonies that sound plain and simple at one moment, and dissonantly involved the next, are all present. As in all that Copland essays, the writing is forceful and expert. The choral portion is even more driving in its nature, and works up to an impressive, jubilant apotheosis of emotion and big sound. Whether the Canticle of Freedom is simply a well-wrought occasional piece or something of greater and more enduring value only time can tell us. But after a single hearing you can say that it does have a certain ring of authority.

Well, time has passed its judgment, perhaps a little unfairly. While it may not be quite at the level of Appalachian Spring, Fanfare for the Common Man, or Rodeo, the piece is certainly worth a listen. Here’s a clip.