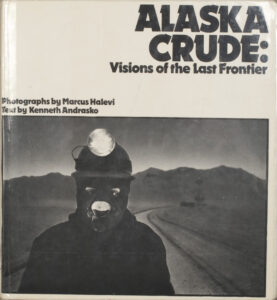

North America’s largest oil field was discovered in Prudhoe Bay on Alaska’s North Slope in 1968, just 9 years into Alaska’s statehood. The discovery unleashed a heated environmental, legal, and political debate unprecedented in the state’s brief history. It took the shock of the 1973 oil embargo – and the accompanying sharp rise in crude oil prices – to clear a legislative path that would enable oil drilling, and ultimately, the construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline.

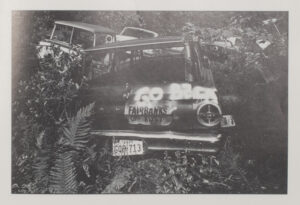

Stretching 800 miles, from north to south coasts, the pipeline took less than four years to build. As people flooded into the state – some temporarily, some to stay – thousands  were permanently displaced by the construction. New economies were invented as old ones were subordinated or eliminated entirely. Alaska Crude unflinchingly depicts this moment of flux in both words and pictures. As author Kenneth Andrasko says himself, the book presents “the paradoxes of Alaska in the throes of modernity.”

were permanently displaced by the construction. New economies were invented as old ones were subordinated or eliminated entirely. Alaska Crude unflinchingly depicts this moment of flux in both words and pictures. As author Kenneth Andrasko says himself, the book presents “the paradoxes of Alaska in the throes of modernity.”

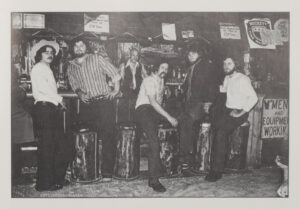

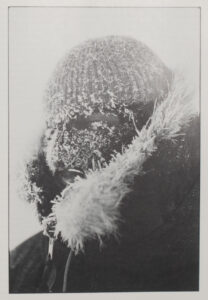

Though intended to be a survey of people  rather than the land, the authors found it impossible to separate one from the other. The hulking physicality of Alaska permeates each of Marcus Halevi’s images, whether it’s a bear dwarfed by a construction site, or a group of young men in a bar staring back suspiciously at the photographer.

rather than the land, the authors found it impossible to separate one from the other. The hulking physicality of Alaska permeates each of Marcus Halevi’s images, whether it’s a bear dwarfed by a construction site, or a group of young men in a bar staring back suspiciously at the photographer.

Alaska Crude would have succeeded as a book of images with no text or as an illustration-free essay, but it works best with both. The combination of text and image communicates simultaneously the growth, destruction, exhilaration, and anger of the times. By portraying a specific, critical moment with honesty, Andrasko’s words and Halevi’s images reveal universal and timeless truths.