Published: Cambridge, Mass., 1988

The 1980s were a terribly dark time for large segments of American society. A mysterious, almost uniformly fatal illness was killing people, most of them young or in their prime. Because the syndrome decimated the immune system, its symptoms were wide-ranging, and those it affected suffered from numerous infections and maladies that had never before been seen in otherwise healthy people. Most of these opportunistic infections manifested with a cruel intensity, leaving those with the syndrome susceptible to blindness, disfigurement, lymphoma, and other dreadful ailments before they finally succumbed to what was, at the time, an almost inevitable death.

Against this backdrop, and in reaction to the government’s inability (or unwillingness) to respond in a manner befitting the scope of the disaster, the communities most affected by the crisis banded together in various ways to address it themselves. AIDS service organizations were created in major cities to provide support and quell hysteria. Activists formed ACT UP chapters across the United States. Writers penned memoirs, plays, essays, and editorials. The visual arts community produced hard-hitting graphics intended to shock the viewer into a realization of what was occurring around them.

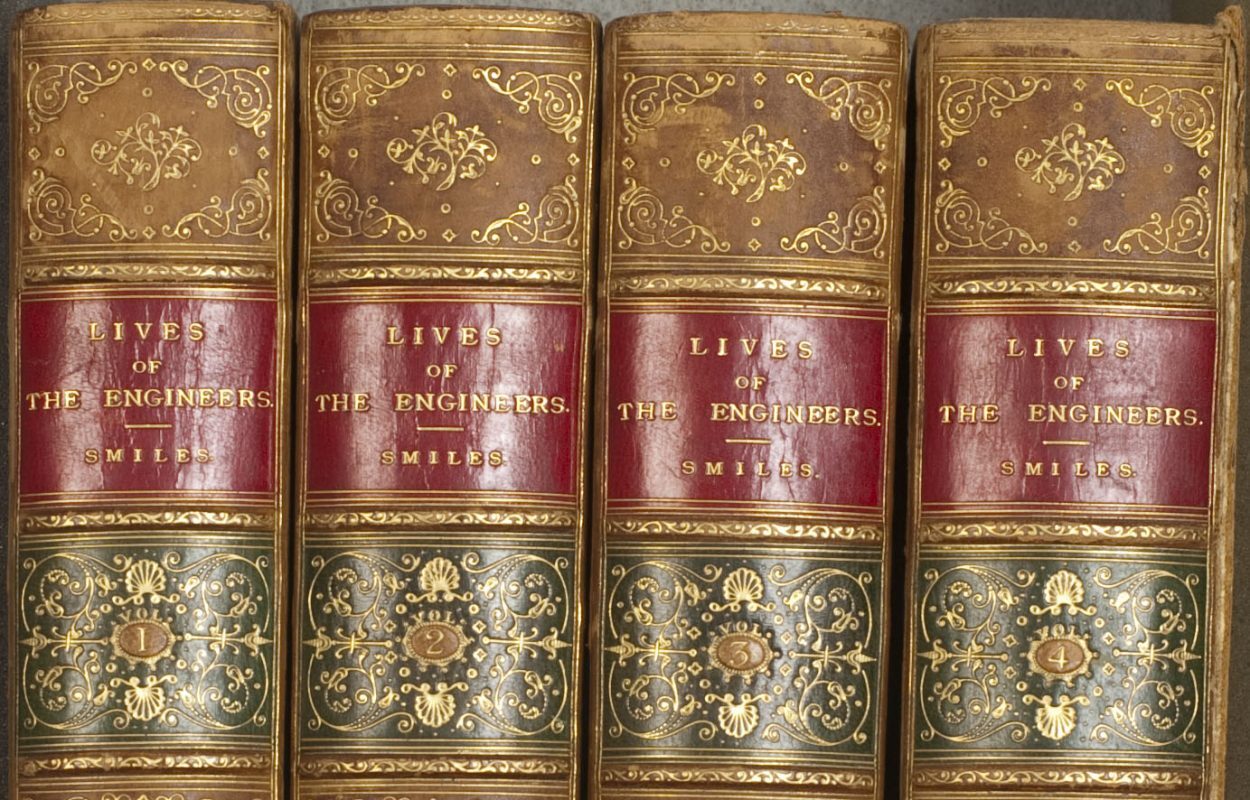

T he Winter 1987 issue of the MIT Press publication October, a journal covering “relationships between the arts and their critical and social contexts,” was dedicated entirely to the AIDS crisis, its social implications, and the cultural response. The issue found a large audience, and the MIT Press republished it as a monograph in 1988. In book form, AIDS: Cultural Analysis, Cultural Activism sold well enough to go into multiple printings.

he Winter 1987 issue of the MIT Press publication October, a journal covering “relationships between the arts and their critical and social contexts,” was dedicated entirely to the AIDS crisis, its social implications, and the cultural response. The issue found a large audience, and the MIT Press republished it as a monograph in 1988. In book form, AIDS: Cultural Analysis, Cultural Activism sold well enough to go into multiple printings.

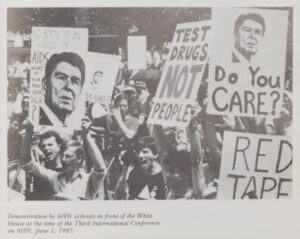

The essays by scholars and social critics cover a lot of ground. Medical nomenclature receives a going-over, as does the fight over who deserved bragging rights for having isolated the virus that causes the syndrome. (When the dust settled, it was agreed that both France and the United States had – surprise! – identified the so-called “AIDS virus” at the very same time.)

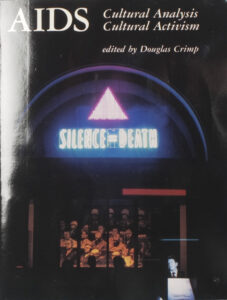

The centrally important role played by visual artists within the AIDS activist movement, including the impact of the iconic “Silence = Death” poster, is examined. Another essay analyzes the ugly spectacle of blaming and vilification perpetrated by the media, including the “responsible,” mainstream press. And an analysis of “keywords” reveals the intense power wielded by such neutral-sounding terms as “family” and “general population.”