Published: North Adams, Mass., 1877

Published: North Adams, Mass., 1877

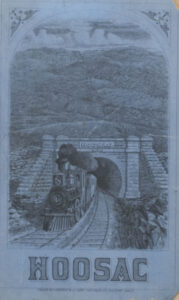

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of the railroad during the 19th century. As it shrank physical distance with land speeds that were unprecedented in human history, rail transportation revolutionized the mobility of people as well as of material goods. But there are certain landscapes that rails cannot efficiently traverse: mountains, for example, get in the way of trains, which don’t like steep grades. As a result, tunnel construction became a widespread and crucially important engineering pursuit in the 1800s.

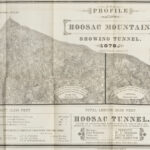

Construction of the Hoosac Tunnel in the Berkshires exemplifies the ingenuity, the expense, the political will, and the sheer tenacity required in such an undertaking. The tunnel through Hoosac Mountain  is just under 5 miles long. Its active construction period consumed roughly a quarter-century and cost at least $17 million in 1870s dollars – an enormous sum. Its builders confronted multiple difficulties (not the least of which was “demoralized rock, or porridge” at the mountain’s western end), and one work interruption was years long. As in similar enterprises, the work was dangerous: nearly 200 people were killed during the course of construction, and many of the deaths were horrific.

is just under 5 miles long. Its active construction period consumed roughly a quarter-century and cost at least $17 million in 1870s dollars – an enormous sum. Its builders confronted multiple difficulties (not the least of which was “demoralized rock, or porridge” at the mountain’s western end), and one work interruption was years long. As in similar enterprises, the work was dangerous: nearly 200 people were killed during the course of construction, and many of the deaths were horrific.

The individuals charged with building the tunnel were open to new ideas, and were quick to embrace novel tunneling methods. Between 1851 (when construction commenced) and 1865, the drills were hand-powered, and the explosive used for blasting was “ordinary black powder.” But the builders were happy to adopt “machine drills, driven by compressed air” as soon as they became available. At about the same time, “experiments were being made with nitro glycerine,” and that innovation, too, was adopted.

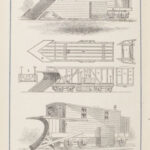

This small booklet seems to be directed at two distinct audiences: it contains a stirring yet fairly technical history of the tunnel’s construction, but it also invites the general tourist to visit the two portals of this “royal pathway.” Visitors to the east end will pass through  “forests of birches” on their approach to a “grand outlook.” Those fortunate enough to visit the western portal will “exclaim with delight at the striking beauty of the scene.” The advertisements in the booklet also seem directed at both the railroad operator (Heywood’s Patent Snow Plow) and the casual traveler (comfortable inns in Troy, New York and North Adams, Massachusetts).

“forests of birches” on their approach to a “grand outlook.” Those fortunate enough to visit the western portal will “exclaim with delight at the striking beauty of the scene.” The advertisements in the booklet also seem directed at both the railroad operator (Heywood’s Patent Snow Plow) and the casual traveler (comfortable inns in Troy, New York and North Adams, Massachusetts).

Though the Hoosac Tunnel’s two tracks have now been reduced to one, freight trains continue to travel through it in the 21st century. An important engineering triumph in its day, Hoosac continues to fascinate. The tunnel and its history are the focal point of the Western Gateway Heritage State Park in the Berkshires. And it’s the subject – or obsession – of several fan sites on the World Wide Web.